$12M landfill upgrade proposed

By Kevin O’Brien

Marathon County’s landfill could one day become a hub for fighting so-called “forever chemicals” under a $12 million proposal to install a reverse osmosis treatment center available for regional use.

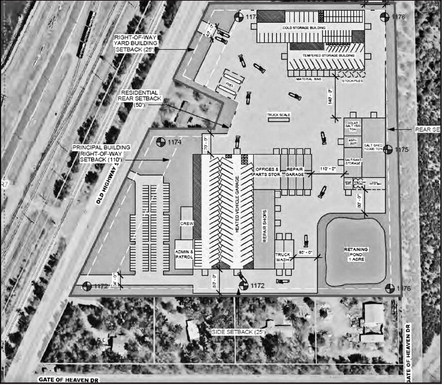

Dave Hagenbucher, director of the county’s Solid Waste Department, spoke to the Environmental Resources Committee last week about an ambitious plan to address leachate, a liquid runoff that accumulates at the bottom of landfills. At the county’s disposal site in the town of Ringle, a liner system is used to collect the contaminated water and remove it so it can be treated off-site at a wastewater treatment plant.

However, because the leachate contains PFAS from household items like water-resistant clothing, packaging and nonstick pots and pans, many wastewater treatment facilities are reluctant to accept landfill liquid, Ha-

See LANDFILL/ page 3 Landfill

Continued from page 1

genbucher said. PFAS don’t break down, and can end up in the water supply even after they’ve been through a treatment process, he said.

Right now, Marathon County hauls its leachate to treatment facilities in Plover and Stevens Point, but if those facilities were found to have a PFAS problem, Hagenbucher said those utilities could stop accepting the leachate without much warning. This has already happened with Wausau’s wastewater treatment plant, and before that, a paper mill that had been working with the county landfill for 40 years backed out of its treatment arrangement in 2019, he said.

Plover’s treatment facility currently accepts four loads of leachate per day (6,600 gallons each), and Stevens Point takes another two loads, Hagenbucher said.

“If we need to haul out more than six loads, we really don’t have a home for it right now,” he said. “It’s really just going to have to sit where it is. We’re going to have to watch it closely and monitor our levels and make sure it doesn’t accumulate on our liner systems.”

With the landfill generating 10 million gallons of leachate per year, the county spends nearly $1 million on treatment plus hauling costs, he said.

Eight different treatment plants, including one as far away as Green Bay, have declined to accept the landfill’s leachate. Hagenbucher said he doesn’t really blame them because of the possibility that PFAS could end up in effluent or in the biosolids spread as fertilizer.

Since technologies for destroying PFAS are still in the experimental phase, Hagenbucher said his department has considered several options for removing the chemicals and sequestering them so they don’t enter the environment. Reverse osmosis, a treatment process that’s been around for decades, could be done entirely on-site, with the remaining liquid going into an infiltration basin, he said.

Even though reverse osmosis has a higher upfront cost, Hagenbucher said the Solid Waste Department could save money over the long run by avoiding hauling costs. If the county were to build a facility that could treat waste from other landfills and industries in the area, he said the cost would be $12 million. If it was just for Marathon County, it could be built for $3 to $4 million less, he added.

Unfortunately, Hagenbucher said the department does not have money set aside for such a project, so it’s looking for an environmental loan that would be paid back with increased tipping fees for those who use the landfill. Last October, he said his department submitted an intent to apply for a loan through the DNR’s Clean Water Fund Program (CWFP), and on March 31, a draft plan for the reverse osmosis system was provided to the DNR.

The full application is due by October of this year, but before it is submitted, he said a public comment period will need to be held this month, followed by a required public hearing sometime in June. After receiving feedback, Hagenbucher said he would return to the ERC for a recommendation, and eventually, the full county board would have to approve the CWFP loan application.

Hagenbucher said the county could qualify for as much as $2 million in principal forgiveness (grants), and also tap into funding available for “emerging contaminants,” which has become widely available. The Solid Waste Department has also submitted an application for congressionally directed spending through Sen. Tammy Baldwin’s office and is exploring the possibility of an Innovation Grant and funding through the State Building Commission.

As a member of the DNR’s advisory commission on PFAS, Hagenbucher said he realizes the problems posed by forever chemicals cannot be solved by separate entities acting independently of each other.

“We need to recognize this as a systemic issue,” he said. “We need to look at it holistically, and not just solving our problem, but solving the problem for the entire community.”

ERC members seemed generally receptive to the idea, with supervisor John Kroll saying he would like to know more details about the proposal. When Kroll asked about what kind of staffing and specialized training would be needed, Hagenbucher said he’s confident that assigning three qualified people to run the reverse osmosis facilities would work.

Board chairman Kurt Gibbs asked Hagenbucher how much extra capacity the facility would need to treat waste from outside entities and wondered what the business model would be to make sure the operation covers its costs.

Hagenbucher said the county’s landfill currently generates an average of 33,000 gallons per day of leachate, with that number rising as high as 70,000 gallons during heavy rain events. To accommodate outside customers, they’ve looked at designing a facility with a capacity of 100,000 gallons per day and a holding tank that would allow incoming waste to enter the system gradually.

As far as potential customers, Hagenbucher said closed landfills generally produce the most leachate, but there are only a few in the area, so he expects only about one load per week. Active landfill sites could potentially be expected to bring in two to three loads per day, he said.

When asked about partnering with other counties, Hagenbucher said he’s also reached out to Portage and Shawano counties, which already deliver solid waste to the landfill in Ringle. He said they may be charged additional tipping fees to offset Marathon County’s costs.

“That’s something we certainly need to consider,” he said. “It shouldn’t all be put on Marathon’s shoulders if it’s truly a regional facility.”

Hagenbucher was also asked about the potential timeline if the county board were to sign off on a loan application and the county was granted funding.

“There’s a high likelihood that we get the funding next year and potentially start building next year,” he said. “Could it be ready to go in the fall of 2026? Maybe, but that would be pretty aggressive.”

Still, both Hagenbucher and county administrator Lance Leonhard said that a lot of effort needs to go into developing a business plan so that the landfill can recover its costs without driving away customers due to higher tipping fees. Leonhard said revenue from the landfill’s new renewable gas collection facility could possibly be used, but he would rather see that money going to offset existing operational costs. Among other things, Leonhard said the Solid Waste Department needs to come up with a price point on tipping fees that doesn’t deter customers while also ensuring that Marathon County doesn’t end up subsidizing treatment for other counties.

“If we’re ultimately going to go down this path, it’s a lot of work,” he said.

Manure plan update

County conservationist Kirstie Heidenreich and conservation analyst Matt Repking updated the committee about a group of 25 farmers and others who are working on a compromise for removing phosphorus from local waterways. The working group was formed after Conservation, Planning and Zoning proposed restrictions on winter manure spreading, which did not go over well with small farmers.

Heidenreich said all of the group members agree that more emphasis should be placed on nutrient management plans (NMPs), which provide individualized guidance for landowners on when and where to spread manure to minimize runoff. About 60 percent of the county’s cropland is already covered by NMPs, which is twice the state average, but Heidenreich said more can always be done.

“Everyone in the work group agrees that this is an idea we need to somehow work into the ordinance, or think of a creative way to make that part of the solution,” she said.

Repking said there’s also support for promoting buffer strips and ground cover, such as corn stover and other residue, to stop or slow the flow of manure when it’s spread on fields.

“Farming is a leaky system, so can we minimize those leaks as much as possible?” he said.

Basing any winter spreading restrictions on the number of animals was also an idea that came up during the group’s first two meetings, Repking said.

Heidenreich said the group has spent a lot of time going over data on phosphorus levels and will continue to meet regularly to work toward solutions.

“I am very proud of this work group,” she said. “It is challenging to come into a room where you know you’re discussing things where some people are adamantly for it and some people are adamantly against it.”