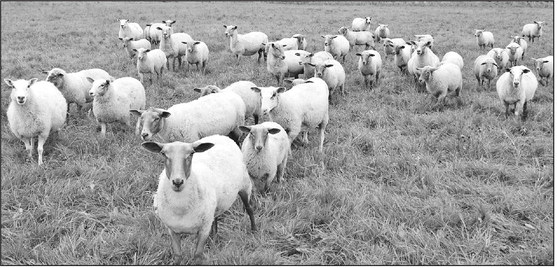

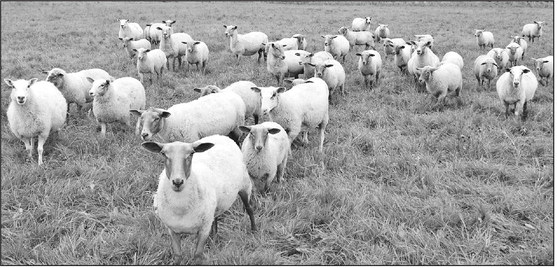

An evening at Half Moon Hill

Town of Hamburg couple share their experiences as sheep grazers

A small group of grazers gathered at Gerrid and Sadie Franke’s farm last Thursday evening to check out the herd of sheep living on one of the many picturesque pastures sprawling across northern M...