50 years later, a martyr is remembered

No one would have thought poorly of Michael Cypher had he chosen to stay in the United States in 1975.

No one would have thought twice had he asked for an assignment to serve some parish community in the United States after having served a year as a missionary in Honduras and suffering a severe blood infection.

Many would have considered it a reasonable and logical thing to do given the rising political unrest in Honduras and specifically the growing threats against missionaries and clergy members in the region at that time.

Anyone who has grown up on a farm knows that there is always work to be done. There are animals to be fed and watered, cleaning and repairs to be done and long hours before you can rest.

Perhaps this ingrained knowledge that his work was unfinished is what opened Friar Casimir Michael Cypher to answer the call to return to Honduras knowing that he faced at best persecution and at worst physical harm and the potential of death as he worked to serve the needs of his rural parish.

On June 25, 1975, Friar Casimir was arrested, tortured and executed by soldiers in Honduras becoming a martyr in that nation’s social and political unrest.

Fifty years have passed since that horrific day, but the memory of Friar Casimir’s sacrifice has not been forgotten among the people he served and in the parish he helped build.

Each year, the people of the region remember his martyrdom and those who died with him with processions and special services. Shrines to his memory and the memory of others who fell on that dark day hold places of honor in churches in the region and in people’s homes.

For the past six years efforts have been actively underway within that diocese and here in Medford to have him formally canonized and recognized as a saint in the Catholic Church.

“The church teaches that every Christian is called to be a saint. Every person is called to be holy as God as holy to love, as God loves, to live as God lives, and that's what a saint is,” said Father Patrick Mc-Connell of Holy Rosary Catholic Church. He said there is value in knowing that farm boy from Medford can walk that path giving the example to everyone else that they too can answer the call.

Michael Cypher was born on January 12, 1941.

He was the 10th of 12 children of Lawrence and Elizabeth Cypher on a small farm near what is now Black River Golf Course. He grew up as part of the Medford community, walking the same streets that people still walk, and seeing the same sunrises over the courthouse dome and the same lazy meandering path of the Black River through the community.

Like most farm families of the time, the Cyphers lived simply, humbly and devoutly. When he was old enough, he attended school at Holy Rosary Elementary School. Accounts of his time in school describe him as, at best, an average student but one who loved physical labor and working with his hands.

He answered the call to serve the church and at age 13 entered the seminary. He was ordained in 1968 as a Conventual Franciscan with the goal of being a missionary. After his ordination and taking the religious name of Casimir he was assigned to a parish in Illinois, but felt called to missionary work serving the poor, struggling people in Latin America. From Illinois, he was transferred to a Spanishspeaking parish in Hermosa Beach, Calif. in order to become familiar with the language.

In 1973, Friar Casimir traveled as a missionary to Gualaco, Hondurus, a small town in the department of Olancho. The area was poor. Most of the residents were peasant farmers known as campesinos who labored for the rich cattle ranchers of the region.

Friar Casimir was given the task of visiting the remote communities serving and bringing the sacraments to his parishioners, no matter how humble they were.

After a year there, Friar Casimir contracted a blood infection and had to return to the United States for treatment. At the time, there was growing unrest as the rich ruling class opposed the reforms being fought for by the peasants and the church.

Foreign missionaries were warned to stay out and were actively being pushed from the country. Friar Casimir, instead, went back to serve the people he had grown to love. He was appointed pastor for San Esteban, a town not unlike Gualaco, that was similarly poor.

“He went there to serve and that’s where he died, serving the people,” Mc-Connell said. McConnell and Dan Brandner, a cousin of Friar Casimir, recently returned from Honduras where they walked the paths he walked and participated in services marking the 50th anniversary of his martyrdom.

“It was really powerful to be there,” Mc-Connell said. He noted that the memory of Friar Casimir and his sacrifice is very much alive in that area and that the cathedral was full for the 50th anniversary service that was held at 11 a.m. on a weekday.

McConnell explains that Friar Casimir was not a revolutionary leader, he was a missionary serving the needs of his parishioners. On June 25, 1975, he happened to be in Juticalpa, the capital of Olancho, getting a vehicle repaired and stayed overnight at the bishop’s residence there. While there, he celebrated a mass for members of the local affiliate of the National Peasants Union before a march calling for land reforms.

Friar Casimir and the men with him were arrested, stripped of their clothing, suffered tortures and were taken to a nearby farm where they were killed and their bodies thrown in a well and then the well was blown up. Friar Casimir’s remains were later recovered and he was buried on July 20.

McConnell described the experience of being where Friar Casimir lived and died as being immensely powerful.

“I literally walked the path that he walked before he was killed. I was in the rectory that he was in before he went over, to help the farmers that were being attacked by the military. I was at the place he was killed,” McConnell said.

“I literally stood in the stairwell, where there's bullet holes still in the walls where they tortured him and the other farmers and other people. I was there in the place where this man ultimately laid down his life. I was in the parish that he helped build,” McConnell said.

McConnell said the most powerful thing for him is to try to understand why Friar Casmir chose to go back, knowing the potential fate that awaited him.

McConnell said he spoke with the man assigned by the bishop of region to head up the efforts to have Friar Casimir declared a saint. He told him that Friar Casimir had the choice to remain in the United States and that he had returned to Honduras because he needed to be with his people.

“He knew that it was dangerous, he knew that is was risky, and then he came back still to serve them,” McConnell said.

“He wasn't trying to overthrow the government, he was just trying to serve the people. And that's why he died,” Mc-Connell said.

Friar Juan Pagoada of Honduras, who is Vice Postular for the Cause and the person who is working to build the case for Father Casmir’s canonization, is coming to Medford this weekend to participate in a special service at 10:30 a.m. on Sunday, July 20 at Holy Rosary Church in Medford to mark the 50th anniversary of Friar Casimir’s funeral.

The case to present to the Vatican is nearly complete and Friar Juan is coming to this area looking for the remaining piece about Friar Casimir’s life when he was just Michael Cypher of Medford.

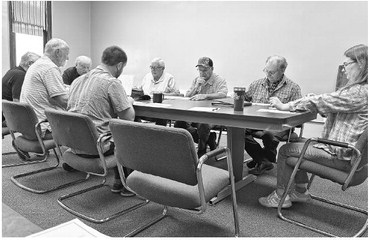

“He’s done all the research he can in Honduras, he needs more information from here,” McConnell said, noting that the case has been worked on for more than six years.

McConnell said that in order to complete the case, there needs to be details and first-hand accounts of Friar Casimir’s life in Medford before he left for the seminary. He said they need contact information for anyone who might have known Friar Casimir when he lived in Medford so that they can reach out to them in the future.

“Our hope is to make the Holy Rosary office kind of the point where if you have information, either first-hand encounters with Friar Casimir, or any kind of stories or memories of him at all can be collected,” McConnell said. He said even small details like how he used to enjoy playing at recess are important.

McConnell said that there is no doubt in his mind that as a martyr Friar Casimir is a saint.

He noted the importance of saints is not to glorify the individual.

“It is always about the faith of the people. The reason we name saints is so that their lives can be witness to other people and that they help us, as a kind of light to those around them. That’s the main purpose, always” McConnell said.

If canonized, Friar Casimir will be the first saint from Honduras and from Medford.

“It’s very clear that he lived his life as a powerful witness,” McConnell said, noting that being a local farm boy from the Diocese of Superior, it is inspiring to learn about Friar Casimir’s life and eventual martyrdom.