Professor gives window into life of refugees

Refugees face a reality unlike what most of us have ever experienced. By better understanding the plight of refugees, we can cultivate a greater sense of empathy and consequently, come up with better solutions to help them, argues Dr. Khalil Dokhanchi, professor and department chair for the Social Inquiry Department at UW-Superior.

“Helping refugees does not mean you have to adopt one as your neighbor. We can help refugees through hundreds of different ways. We can help refugees return home. We can help refugees in neighboring countries and we can help them come here. So there is no single solution. You choose what you want,” said Dokhanchi, who spoke at The Highground near Neillsville on Sept. 21, which is also the International Day of Peace.

Dokhanchi came to the U.S. from Iran in 1977. Although not a refugee himself, he has an interest in sharing refugees’ stories. His research interests include peace-building in post-conflict societies, international humanitarian law, and war and peace in Bosnia, Northern Ireland and the Middle East.

The first step in learning how to best help refugees is simply knowing what a refugee is. Worldwide, 103 million people have been forcibly displaced. That number is larger than the population of France, Great Britain or Germany. However, of those 103 million, only 32.5 million are considered refugees and only 5.3 million are in need of immediate resettlement.

The legal definition of a refugee was established in 1951. After World War II, two populations were “stuck,” said Dokhanchi, European Jews and Eastern Europeans.

“The Jewish population, they do not want to stay in Europe, because they argue that their neighbors turned against them. So, for example, if you are a Jew from Poland, you don’t trust necessarily your neighbors and you don’t want to go back. So you have that population residing in Germany and you don’t know what to do with them. And clearly they did not want to stay in Germany. And not all Jews, but some,” he said.

“The second population is Eastern Europeans. Just about after the second World War, the Russians took over all of Eastern Europe. And so a lot of Eastern Europeans tried to escape Communism and ended up in Germany. So you have those two populations and no one knew what to do with them. As a result of this, countries came together and signed what’s called the Refugee Convention.”

The convention, supplemented by the 1967 Protocol, provided the most comprehensive codification of the rights of refugees to-date at the international level. It established the legal definition of a refugee as a person who has a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, social grouping or political opinion. This definition provides the basis for the work of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

Countries that have signed the 1951 Convention are obliged to take in refugees and treat them according to internationally recognized standards. In order for refugees to receive this protection though, they have to prove through documentation that they meet the legal definition of a refugee.

Refugees should not be confused with migrants. According to the UN Migration Agency, International Organization for Migration (IOM), a migrant is any Refugees,

from p. 1

person who is moving or has moved across an international border or within a State away from his/her habitual place of residence, regardless of: the person’s legal status.” Migrants are still entitled to basic human rights, but they can be deported.

The 5.3 million refugees in need of immediate resettlement today fall into specific demographic groups that make them more vulnerable. For example, they may be elderly, young children, LGBT or domestic violence victims. To put that 5.3 million number into perspective, Germany accepted 1 million refugees just in 2015. There are 3 million refugees currently living in Turkey and 2.5 million living in Pakistan.

“So this is not impossible to deal with. It’s possible that this can be done,” said Dokhanchi.

He said that part of the difficulty in teaching about refugees lies in helping people understand how it is that refugees end up arriving at their destination country’s borders with little to no resources.

“We have very little empathy sometimes,” said Dokhanchi.

In hopes of changing that mindset, Dokhanchi came up with a game he plays with his students that simulates life as a refugee. The game involves the “refugee” rolling the dice to determine their life circumstances, whether that’s losing a job, getting robbed on the way to a new country, having to sell one’s passport to buy food, getting stuck in a country due to visa issues, or any number of other possible outcomes.

“There is no certainty, no singularity. Every single one of us will roll the dice… There is no guarantee. This is not a guaranteed process where you start at point one and end up at point two,” said Dokhanchi.

He gave some examples to illustrate. For one, in Afghanistan the Taliban recently ruled that women can no longer serve as judges. The situation in that country has deteriorated over the last two years, to where girls cannot go to school or university, or hold most public-sector jobs. A woman who recently lost her job may be forced to move to another country to support herself or family members.

“People just don’t get up one morning and say ‘I wanna go to the United States’ and leave the country. There is something called the push factor… If you can’t make a living, you have to leave. If you have children, you have to feed them,” said Dokhanchi.

When people make the decision to leave their home country, there are many barriers to successfully reaching their destination. Often limited to whatever they can carry on their back, refugees walk hundreds of miles in hopes of being admitted into a freer country. With the advent of smartphones, for the first time ever people began using Google Maps to walk to a new country.

“That was the breaking point in 2015 for Europe, because usually the patterns of migration are very controlled. You go to a border town, you show your passport, you enter. If we take, for example, Minnesota, people don’t expect you to go the Boundary Waters, get on a boat and go across. Imagine what happens if 200 Americans went through the Boundary Waters into Canada and said they were seeking political asylum. The Canadians would freak out. That is the same thing that has happened in Europe. People are using irregular modes of entry. They aren’t traveling on the major roads; they are just walking and end up in the country.”

That isn’t to say the journey is easy; rather, it’s often long and treacherous. Refugees may be injured going through rough or unsafe terrain. For example, thousands of unmarked landmines are scattered throughout Afghanistan. Since 1989, about 56,923 Afghan civilians have been killed or injured by landmines and explosive remnants of war. The United Nations Mine Action Service estimates some 4,158 hazards remain, representing nearly 463 square miles.

Sea travel presents its own dangers. Every year, about 3,000 to 4,000 people drown in the Mediterranean while trying to migrate to another country. Most of those are people traveling from North Africa to Europe. In June, an overloaded fishing boat carrying migrants from Pakistan, Syria, Palestine and Egypt sank approximately 45 nautical miles off the coast of Greece, with more than 500 people presumed dead.

There is no guarantee as a refugee that the ship you’re on will make it to land.

“If you look at Europe, for example, what they are doing is absolutely horrendous. They are essentially saying, ‘We don’t want refugees to come to Europe,’ so they are making deals with, for example, Libya, Morocco and Egypt. Libya is getting their coast guard from the EU. So what the EU is saying is, ‘Libya, you get yourself these ships. Make sure the boats never get to our ground.’ If they do it, they have to consider them as refugees and they have to accept them. So the best way is to make sure they never even set foot. So that’s why boats are sinking because they are never allowed to land.”

A similar phenomenon has happened in Australia. For example, although Christmas Island is an Australian territory, Australia has declared the island to be outside the Australian migration zone. There is a refugee processing center on the island. But, if you arrive there as a refugee, you are not guaranteed admission because it’s “non-Australian.”

“They (the Australians) pay Indonesian captains money to take the money from the refugees, go around the island (and) drop them back where they came from,” said Dokhanchi.

Another danger of travel is running into bad actors who take advantage of desperate people.

“For example, if you’re coming from Mexico to the United States, people talk about coyotes. These are people traffickers. They take your money… If you don’t have your passport, you can’t go to the police and say, ‘This man took $4,000 from me to take me illegally across the border and stole my money,’ because then they just ship you back to your country and may not do anything about this person that stole your money. Most of the time, there’s also corruption, so they may have paid off the local police officers, and nobody wants to change the system.” Other dangers of travel include being sucked into labor trafficking or sex trafficking. Many refugees cannot gain legal status and the means to earn an income, making them especially vulnerable to smugglers. Smugglers may demand more and more payment from refugees in order to reach their intended destination, and when the refugees can’t pay, they are subject to physical or sexual abuse.

If a refugee manages to successfully reach the country they are trying to enter,

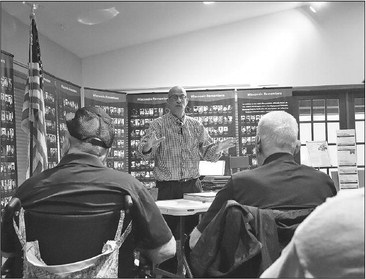

Dr. Khalil Dokhanchi, professor and department chair for the Social Inquiry Department at UW-Superior, speaks about the challenges refugees face. Below is a month’s worth of supplies that a refugee family may typically receive from the United States Agency for International Development, including sanitary napkins, toilet paper, a lantern and hygiene items.

VALORIE BRECHT/STAFF PHOTOS

from p. 6

their challenges are far from over. There may be financial barriers to enter the country. For example, Dokhanchi said the last time he checked, each person entering Germany to live had to pay $8,000; so for a family of four, it would cost $32,000.

Depending on the country you go to as a refugee, you may be stuck in a refugee camp for an indefinite amount of time until the government finds somewhere to put you.

“In some places, they may think the refugees are a destabilizing force, so you have to stay in the camps. The good thing about camps is if you want to get rid of them (the refugees), you just close the camp and push them out,” said Dokhanchi. “You don’t have to track them down like you would if they were scattered all throughout the city.”

Oftentimes, refugees have left all their costly possessions behind and spent all their money just to make it to the new country, so when they get there, they have to survive on whatever resources the government can provide. The United States Agency for International Development provides food rations for refugees. The daily ration for an individual is 400 grams of rice, 60 grams of beans, 15 grams of sugar, 5 grams of salt, 100 grams of wheat and 25 milliliters of oats. That is not a guarantee, either.

“It all depends on how much funding is available. If the funding is at 60 percent, you get 60 percent of that,” said Dokhanchi.

Financial assistance may be limited or non-existent, depending on the country. As an example, Syrian refugees in Turkey receive a pre-paid gift card for $29 per person per month.

Refugees also have the challenges of possibly learning a new language, finding a job, locating housing, enrolling their children in school, applying for governmental assistance programs, learning to navigate the local transportation system and much more.

For the U.S., it is an 18- to 24-month process for refugees to be integrated into the country, starting with a series of interviews and checks by the National Counterterrorism Center, FBI, Department of Homeland Security and State Department before they are approved to stay here.

“So my point is, yes, I’m cognizant of the fact that you want to have security, and that’s a very legitimate thing. I am an American. I’d love to have a flight that is safe and I’d love to live in safety, so I’m not trying to say that nobody is entitled to this. But the issue is, can we have safety and sympathy for refugees? And I would argue that we can (have both),” said Dokhanchi.

He also gave examples of people groups that had successfully settled here and contributed to society. For one, there is a large Somali population in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area and many of them work at the airport.

“Now if you find incidents of terrorism, point it out to me. But look, they have been working hard to improve their lives for almost 30 years. Not a single case of terrorism involved. So we can live in peace.”

He also referenced the Hmong people, who first began arriving in Wisconsin in the late 1970s after the Vietnam War. Initially, there were high levels of poverty and high reliance on welfare among the Hmong people.

“But now you are seeing, for example, at the state level, Hmong people are running for office. Financially, they are better off… They are no longer dependent. You can look at the second and third generations of Hmong that are actually entrepreneurs and starting their own businesses,” said Dokhanchi.

He asked people to keep an open mind and heart when it came to helping refugees achieve a better life.

“The question is, how do we do this the right way? And like I said, there is no one right way to do this. We could help them in terms of fixing (the) United Nations. We could help them by sending donations to UNHCR. We could help them by adopting them to come to the United States — the choice of action is yours. What you want to do is your choice. But there’s plenty of things that could be done to help the people.”

Statistics and resources Some statistics on the refugee population in Wisconsin are as follows.

— Ninety percent of the state’s refugees live in the Madison, Milwaukee or Green Bay metro areas.

— From 2001-2015, Wisconsin received the most refugees from Burma out of any country. There were 4,320 refugees from Burma in that time period. The next-highest countries of origin were Laos with 3,352; Somalia with 1,181 and Iraq with 1,132.

— From Oct. 1, 2020, through Sept. 30, 2021, Wisconsin received most of its refugees from the Congo, with 238 from that country. The next highest was Burma, with 80 coming from there.

— Between 2001 and 2015, the number of refugees settled in Wisconsin peaked at 2,421 in 2004. It then dropped dramatically and gradually grew since then, with 1,292 resettled in 2015.

— Between 2001 and 2015, 14 refugees were resettled in Clark County. However, 456 were resettled in neighboring Marathon County.

Dokhanchi encouraged those interested in learning more about refugees to watch the documentary “The Flagmakers,” which examines the workforce of the Eder Flag factory in Oak Creek, south of Milwaukee. Most of the people who make American flags at this factory are refugees.

Dokhanchi also has a “Refugee Books” Facebook group in which he recommends various children, teen and adult books that discuss the experiences of refugees. He also gives the suggested grade level for teachers interested in incorporating these books into their curriculum. People can search “Refugee Books Dokhanchi” on Facebook to get connected.

Above is a typical refugee food ration for one day, including 40 grams of rice, 60 grams of beans, 15 grams of sugar, 5 grams of salt, 100 grams of a wheat/soy blend and 25 grams of vegetable oil.

VALORIE BRECHT/STAFF PHOTO