Scotch Creek restoration plans in question

By Kevin O’Brien

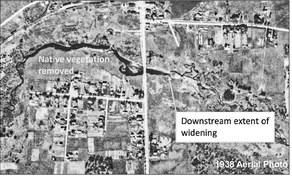

While discussing plans to restore Scotch Creek on Monday, an engineer hired by the village of Edgar faced some pointed questions fr...

By Kevin O’Brien

While discussing plans to restore Scotch Creek on Monday, an engineer hired by the village of Edgar faced some pointed questions fr...