Deputies practice de-escalation on simulator

Clark County Sheriff’s Dept. Detective Noah Lobner is responding to a call where a man with reported mental health issues is agitated and acting out.

Outside on the porch of his home, the man strikes a threatening, aggressive pose, turns his back to Lobner to ask an imaginary someone if he should attack, and then, despite the officer’s warnings, charges. Lobner discharges his Taser and stops the man’s advance.

It could have easily been a real situation, but in this case, Lobner is actually in the training room in the sheriff’s department at the Clark County Courthouse in Neillsville. He’s interacting with a video screen on the MILO Range, a firearms training simulator that instructs officers on ways to handle various situations. In this time when officers around the country are facing backlash for alleged overreactions to circumstances, Clark County brought in the MILO Range to train officers on de-escalation tactics.

Lobner now replays the same call, this time with a different pre-loaded outcome.

On this call, the man again appears to be threatening, but different body language and actions convince Lobner that he won’t attack. This time, the officer is able to talk the man down from his state of anxiety without discharging any sort of force.

All of Clark County’s officers and some from three municipalities in the county trained on the MILO Range in recent weeks. The focus was on de-escalation, Lobner said, to teach officers how to interact with people on calls where they may be angry, drunk, on drugs, or dealing with a mental health problem. If an officer can effectively calm a subject, Lobner said, there will be no need to resort to use of an intermediate weapon such as a Taser, or the extreme use of lethal force.

The MILO Range is owned by the Wisconsin Counties Association, Clark County’s insurance carrier, and offered to members to help them employ strategies that can not only save lives, but reduce a county’s exposure to potential legal liability. Clark County last had the range in 2016.

The MILO Range has dozens of recorded scenarios that are projected onto a large screen with which an officer interacts. It can be used for everything from firearms training to Taser use scenarios to active shooter situations, but this time, Clark County Sheriff Scott Haines wanted to concentrate on de-escalation.

As the department’s firearms training officer, Lobner coordinated the MILO Range sessions. For each officer in the department, he selected a range of scenarios for them to encounter. The “calls” can involve an emotionally disturbed subject, one involving a domestic abuse situation, a subject with a gun, “Whatever we want it to be,” Lobner said.

As the officers encounter the scenarios, Lobner observes their response and later will offer suggestions for possible alternatives. He can even vary the scenario as it unfolds.

“Based off the officer’s reactions, I can select how the scenario is going to continue,” Lobner said.

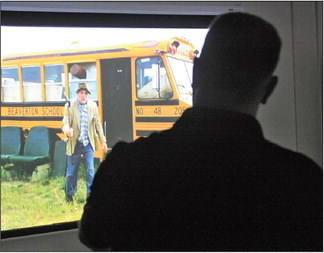

In a training session for Deputy Aaron Ruggles last week, Lobner chose a situation in which a citizen had called to report a man who has illegally moved a bus onto private property and was squatting there and refusing to leave.

As Ruggles arrived “on scene,” he could see the subject in the bus, but he wouldn’t come outside.

Through a bus window, Ruggles could observe the man was holding a long object, possibly a rifle. As he spoke with the subject and tried to coax him outside, he had to decide if the man and the yet-unidentified object posed a potential threat. As the man finally came out of the bus, he was carrying a crutch, not a rifle. The deputy talked the subject down, and the situation was defused without incident.

Dialog and distance were two important factors at play, Lobner said. To de-escalate a situation, officers are shown how to keep a safe distance, so they have time to react if a subject charges them, and to use dialog to ease the tension.

“By creating distance and dialog, you can de-escalate the situation, that’s our hope,” Lobner said.

Distance can be crucial. In one scenario Lobner demonstrated on the screen, he deals with a man holding a knife.

In the first version, Lobner is at the scene with his firearm holstered. He tries to tell the man to drop the knife, but he suddenly charges and Lobner has to draw his weapon and fire. He barely has time to shoot before the man reaches him.

In a second version, Lobner has his firearm drawn right away. When the subject charges, Lobner is much more prepared to shoot, even though it’s only a second more of time. That second can mean the difference between life and death, Lobner says.

Dialog is a tool officers have to master, Lobner said. Treating a person in distress as an equal, rather than trying to intimidate them as an officer, can help defuse a situation.

“Humanize, talk to them like you would your friend,” Lobner said.

In slowing down a situation with dialog, officers can gain more time to assess what’s happening. For instance, Lobner said, if a subject is peering around, he or she may be looking for an escape route to run. Clenched fists mean aggression, and so on.

Lobner said officers can avoid use of force if they can convince a subject they are there to help, not harm.

“We have to be police officers. We have to be psychiatrists. We have to be social workers,” Lobner said. “You learn that through time. The longer you do this, the more you learn how to talk to people.”

With officer use of force so scrutinized recently with the police shootings in Minneapolis, Kenosha, etc., it’s important to keep deputies trained on how and when they should react in various situations. Deadly force is always a last resort, Lobner said, but is justified when an officer or someone else is threatened imminently with great bodily harm or death.

While new recruits are trained on the basics of deadly force use when they graduate, further training keeps them prepared. How much training an officer may get depends on where they work.

“It all depends on budgets or funds and the department’s willingness to send people to training,” Lobner said. “We have a good department here. We rarely get denied a training. Here we’re fortunate that we train a lot. We’ve always trained using the right force at the right time.”

Problems may arise as an officer may not know until the final seconds of a situation how much force may be needed to stop a threat. In the case of a subject in a druginduced psychosis, for example, a 100-pound man can seem to have super strength.

“It can take four guys to restrain that person,” Lobner said.

He also said even the most simple- sounding dispatch to a scene can lead to anything. Even in rural Clark County, anything can happen.

“I’ve been to stabbings, shootings, armed robberies, and it’s not just in one certain areas. It’s all over,” he said. “Nothing is ever the same. In my 20 years of law enforcement, I’ve never gone to the same call. There’s a variation in it.”

And, every officer can respond differently, depending on what presents itself and how they perceive it. Even on the MILO Range, Lobner sees varying reactions to the same situation.

“I get people that are pretty ramped up,” he said. “Everybody reacts differently. We’re all human and we all react differently, and we all react according to our training.”

An important part of the MILO Range training is the debriefing, in which Lobner and the officer review what happened, what may have gone wrong, and options for reacting in the field.

”It’s OK to make a mistake, but we also need to learn from it,” Lobner said.

That learning might save an offi cer’s life, or that of a distressed person whose predicament led to an encounter with police.

Lobner said he talks with the offi cers about the need to be alert and diligent on every call, or when doing MILO Range training, or even when completing required firearms training on a shooting range.

“We stress that complacency can get you killed,” he said. “Train as if your life depended on it.”

There is no point in a law enforcement career when an officer should stop preparing, Lobner added.

“I still go into scenarios and I go, ‘Whoa, what could I do here?’” he said. “I’ll be learning until the day I retire.”

The MILO Range experience is just another way officers can be more prepared to do their jobs, and to react properly in an age when the use of deadly forced is being called into question.

“These are the police issues in the world right now, so we need to focus on this right now,” he said. “We do this to help these guys be better offi cers.”