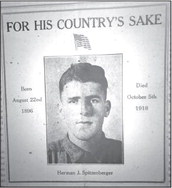

Echoes of a past pandemic

1918 articles show parallels between Spanish flu, COVID-19

The word “unprecedented” is used a lot these days to describe the current s...

1918 articles show parallels between Spanish flu, COVID-19

The word “unprecedented” is used a lot these days to describe the current s...