NEW PLACES TO

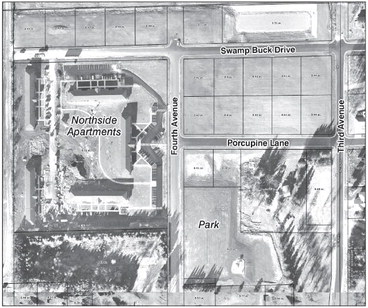

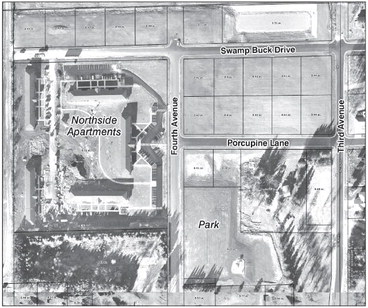

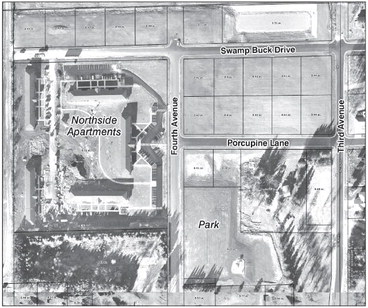

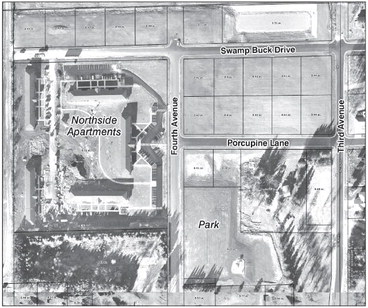

As soon as winter releases its icy grip on Central Wisconsin this spring — and the ground begins to thaw out — city offi cials in Abbotsford are hoping to see signs of construc...

As soon as winter releases its icy grip on Central Wisconsin this spring — and the ground begins to thaw out — city offi cials in Abbotsford are hoping to see signs of construc...