Lee County, Iowa

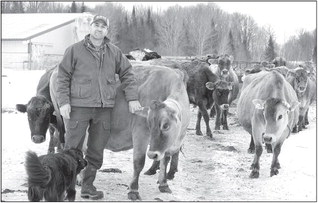

Jim Briggs is a town of Frankfort dairy farmer, milking 56 Jersey cows on an 180-acre farmstead. He is president of the Marathon County Farmers Union chapter.

Briggs and his family, which includes his wife, who has a nursing job, and a son, who attends Stratford High School, came to central Wisconsin in 2014.

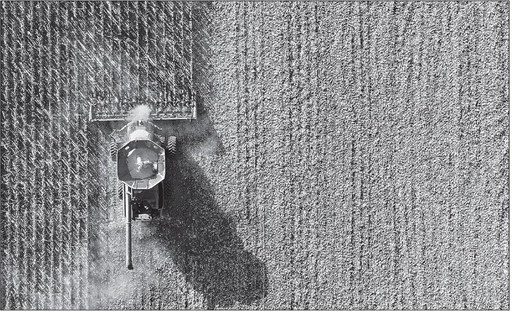

Asked about the future of Marathon County agriculture, Briggs worries that it may turn into a place like the one he left behind in Lee County, Iowa.

It’s a place he says is dominated by industrialized ag. “You have row crops, corn and soybeans,” said. “And hog confinement operations.”

Briggs said this type of agriculture, while perhaps efficient, leaves out the small, independent farmer and devastates what used to be small farming communities.

“One guy with the right equipment can farm 10,000 acres or more,” he said. “You require very little manpower. And a result, you can drive through the small towns down there. They are all boarded up.”

Briggs, who was raised on his father’s dairy and milk bottling operation near Boston, said he moved to western Marathon County from Iowa because you could, as a small producer, still farm and the local downtowns still had some vitality left.

“We moved up here and, holy smokes, a village like Stratford had a car dealership and three gas stations,” he said. “I was impressed, too, with the diversity of agriculture. You had a lot of dairies, but you also had direct market organic producers and ginseng.”

Briggs, sees, however, the shadow of industrial agriculture fall across Marathon County.

“When we showed up here in 2014 there were over 1,000 dairies,” he said. “Maybe there are 500 or less now.”

Briggs sees unrelenting consolidation in the dairy industry. “I think dairy will consolidate unless something is done,” he said.

He said that the Amish and Mennonites are the local dairy industry’s “saving grace,” but, with chronically low milk prices, he doesn’t think a next generation of non-plain-clothed young people will have a way to take over many of the remaining dairy farms.

“Young kids would choose to get into the industry if there was a way to do it,” he said.

Looking ahead another 20 years, Briggs predicted Marathon County would have fewer than 100 dairies. The consolidation will accelerate, he said, as milk processors and retailers, such as KwikTrip, WalMart and Grassland, operate their own dairies.

The problem here, he said, is that Marathon County will run the risk of becoming Lee County.

“What you are left with is cash grain...corn, soybeans, oats and wheat,” he said. “All of that is very low profit.”

This is a problem not just for agriculture, but for the whole rural economy and quality of life.

“My experience is that this impacts the entire economy and the entire community,” he said. “What happens on the farm affects the schools, the fire departments...all things all down the road.”

For Briggs, there is only one answer: supply management. “My unpopular opinion is that we need to balance supply for a profitable demand,” he said.

He said a quota system could work if dairy producers could ever agree to adopt one. The successful supply management system in the cranberry business is proof, he contended.

Briggs understands, however, the political difficulty of ever getting supply management approved as national dairy policy.

The alternative, though, he said, is worrisome. That future is depopulated, low income rural communities like those you find in southern Iowa.

“You have these poor counties,” he said. “Their Main Streets are nothing now.””