Clinton County, Michigan

Mark Stephenson is the director of Dairy Policy Analysis at UW-Madison.

The dairy economist readily admits the Wisconsin dairy industry has had a rough ride for the last several years. He acknowledges the basics. Small and medium sized dairies are shutting down at an alarming, eight percent annual pace. Row crops are on the rise.

Yet, Stephenson is bullish about the state’s dairy industry, particularly the Marathon County dairy industry.

He doesn’t predict the county will turn into an impoverished home to cash grain farmers. Instead, he envisions a Marathon County dairy renaissance.

Stephenson says Marathon County will become Clinton County, Mich.

“Not in the short term, but over the long run,” he clarified.

Stephenson said Marathon County is too far north to grow soybeans and corn competitively, but is able to give dairy cows an optimal 50 degree average temperature for milk production.

“Your county is an ideal region for dairy cows,” he said.

The dairy economist predicted lots of dairy farmers in the next few years may transition to cash grain producers, but, in time, their land will get snapped up once again by dairy producers.

“Any commodity runs in cycles, but, as we’ve seen in the past few years, it’s harder to break even with cash grain,” he said. “Dairy is profitable. Dairy will buy up that cropland.”

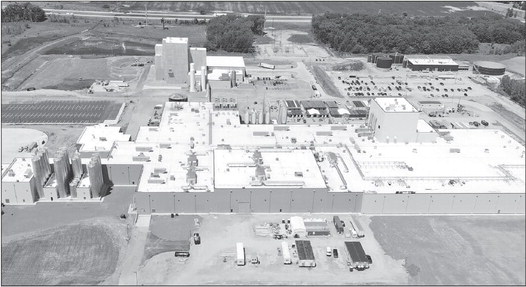

As that happens, Stephenson said, dairy processors will take notice. That’s when Marathon County will turn into Clinton County. This is a county, he said, that is seeing two major dairy processors build facilities in St. John, the county seat.

One facility is a $425 million plant owned by Spartan LLC, a merger of Irish company Glanbia, Select Milk Dairies and Dairy Farmers of America, that will be able to make 800,000 pounds of cheese each day. A second $85 million facility owned by Proliant Dairy will daily manufacture 400,000 pounds of whey permeate powder.

These two plants, said Stephenson, will handle production gains delivered by a quickly growing Michigan dairy industry. That state lost 200 dairy farms last year, but since 2000 has seen its cow numbers increase by 40 percent and its milk production grow by 96 percent.

Michigan’s economic development corporation will give Spartan LLC $26.1 million in tax abatement incentives over 15 years after the cheese plant is completed in December.

Stephenson said a dairy renaissance in Marathon County would not be enjoyed by only large dairies, but dairies of all sizes. “If you look at farm records, we see profitable dairy farms at all sizes of operation,” he said.

Stephenson said current trade wars have recently not been kind to Wisconsin agriculture, but he said the state has land and resources to compete and grow sales in the international dairy market.

“We have a lot of potential,” he said. Stephenson noted that dairy powerhouse New Zealand is “tapped out” for more milk. The same goes for the European Union.

“The United States is in a good position for export sales,” he said.

Stephenson said that while his “crystal ball is cloudy” he sees a potentially profitable dairy industry in Marathon County’s agricultural future. Grant County, Wisconsin

Marathon County agriculture is changing and must change.

That’s the view of Matt Oehmichen an ag consultant at Shortlane Ag Supply, Colby, and a member of the Eau Pleine Partnership for Integrated Conservation advisory board.

Oehmichen sees Marathon County as overly dependent on the dairy industry and, unwilling to diversify into other, more profitable ventures, suffering from poor farm income year after year.

“The average farm income here is under $42,000 a year,” he said, citing USDA statistics. “That is really, really low. Something is seriously wrong about how the cash flows back to farm families.”

Oehmichen said there are a myriad of reasons why dairy and beef sales, which represent nearly 80 percent of the county’s total ag sales, have not generated more profit. They include, he said, industry consolidation, oversupply, trade policies and a worthless Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board.

The answer to this many-headed problem is not to try and fix the dairy industry, he said, but, instead, to embrace regenerative agriculture, which would include raising cash crops, notably small grains like oats and barley, and using money- saving cover crops and no till techniques. He sees possibilities in grazing cover crops with beef or other meat animals.

The goal here, he said, is to transition Marathon County into Grant County, Wis.

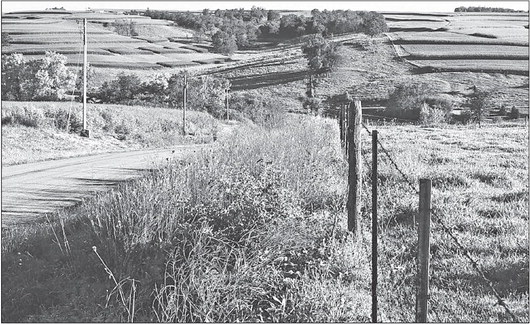

This is a county that milks more cows than Marathon County, but, having a more diverse agricultural base, also produces a significant number of hogs and chickens. Unlike Marathon County, Grant County, which is hilly with some deep ravines, is a state leader in regenerative agriculture, with as much as a third of farms using low-input cover crops and no till practices. The result, Oehmichen said, is more profitable farms. “Marathon County net farm income dropped 12 percent five years after 2012,” Oehmichen said. “But net farm income in Grant County over the same time period increased to $47,382, a 16 percent jump.” USDA statistics indicate that cheaper methods of production helped the Grant County bottom line. The county’s 2017 per farm average production expenses were $142,674 compared to a Marathon County per farm expenses of $149,465. Lower production costs, as well as greater diversity of commodities to sell, may have helped Grant County best Marathon County for net average farm income, $47,382 compared to $41,806.

Oehmichen said Marathon County agriculture is already headed in a more diversified direction, but without much success. Many dairy farms have sold their cows and started raising corn, but this commodity’s market, he said, is flooded and only propped up by government mandates on ethanol. “We have so much grain, we are sitting on a whole year’s crop of corn,” Oehmichen said. Hemp is another troubled alternative, he said. Without factories to turn the hemp fiber into paper, insulation or anything else, the market for the commodity has “quickly flooded” with only a small fraction of production going to therapeutic oil, the consultant said.

Oehmichen said diversification can pay only if it is profitable. That means, he said, use of cover crops to lower the costs of fertilizers and weed control, and no till practices to prevent valuable soil from washing down ditches into creeks and rivers.

“The point here is not bushels to the acre, but, instead, the margins you are making per acre,” he said.

Oehmichen said Marathon County, being flat with rolling hills, would have an easier time adopting no till and cover crop techniques than Grant County, even if it doesn’t have that county’s conservative imperative given how vulnerable its hillsides are to erosion.

The ag consultant said he’s pencilled out savings from regenerative agriculture. It comes to $50 an acre, he said, and that calculates to a $10,600 total savings on an averagesized, 212-acre Marathon County farm.

Oehmichen said said he doesn’t see dairy ever leaving Marathon County, but, given chronic low margins in the dairy business, things are changing, as they must.

“We need a second way to make money,” he said.

FUTURE OF AGRICULTURE 4. A conversation with Dr. Schlesser

Asked about the future, Marathon County UW-Extension agent Dr. Heather Schlesser said this county’s best run and profitable small and large dairy farms will survive this era of low milk prices, but, following the pattern of the last century, many milk producers will “throw in the towel.”

She said Marathon County farmers will make their own future. They won’t necessarily follow the pattern set by Lee, Clinton or Grant counties.

Schlesser said her guess is that the county’s ag future won’t be just dairy. It will be something else. For this new future to be successful, she said it will need the right kind of diversity.

Schlesser said many farmers have turned to corn, soybeans and even hemp to stay in business. Some of these farmers have made major investments in propane-fueled dryers to play the cash grain game. These attempts to diversify, she said, may have helped to keep the barn lights on, but “have not been sustaining.”

Schlesser said, there are untapped markets where farmers might be able to turn a nice profit. Direct marketing of farm goods is a possibility, she said.

The county agent recounts a recent story to make her point.

Schlesser said that three county dairy farmers this year purchased 60 underweight pigs from Iowa, where, due to COVID- 19, they could not be processed, and contracted to sell them as finished hogs to local consumers. “All of the hogs were immediately sold,” she said. “People appreciate buying meat from a local farmer. People want to know where their food comes from.” Schlesser said this story doesn’t predict a huge hog industry in Marathon County, but says farmers can do well taking advantage of the right opportunities, especially when farmers can connect directly with end-consumers.

“There are all kinds of possibilities,” she said. “We are seeing more and more Community Supported Agriculture farms selling vegetables to people. And, if you look just south of us in Portage County, they grow a lot of vegetables for Del Monte and others. Maybe we could grow more vegetables here. You can reach customers directly even as a dairy farmer. Look at Sassy Cow Dairy down in Columbus where they direct market ice cream and milk to people.”

Schlesser said farmers may be wise to engage in multiple enterprises on their farms, producing more than just one commodity, like milk.

She doesn’t necessarily recommend Marathon County farmers raise chickens, but she does advocate a maxim taken from that industry. “Don’t put all of your eggs in one basket,” the county agent said.

Schlesser said moving Marathon County to a more diverse agricultural future will likely be an uphill struggle, but that’s the nature of any change.

“People hate to change,” she said. “We continually fight to stay the same.”

Schlesser said government programs designed to help farmers have kept many hanging on for years but have not reversed consolidation.

In her view, government would do better to assist farmers to change-up their operations rather than try and keep them doing the same unprofitable thing. “Personally, I would vote to push for change,” she said.

She added that government support programs, however, need to be redirected incrementally, not all at once.

“You want to rip off the Band-Aid slowly,” she said.

Schlesser said it is not the place of extension agents to tell individual farmers what to do or what investments to make. These business people, she said, must make their own decisions.

Schlesser said, however, her diversity message does answer Ralph Bredl’s dilemma about whether to make another high-stakes, risky investment in the low-profit dairy industry.

Her advice is basic economics. “One way to mitigate against risk is to diversify,” she said.

Matt Oehmichen

Dr. Heather Schlesser