Battle of the Bulge, as seen close-hand by local veteran

By Ginna Young

For most, it’s something that’s read about in the history books, as what could be the biggest, bloodiest exercise in American history – what is known as the Battle of the Bulge. For Clifford J. “C.J” Moore, Bruce, it was all too real.

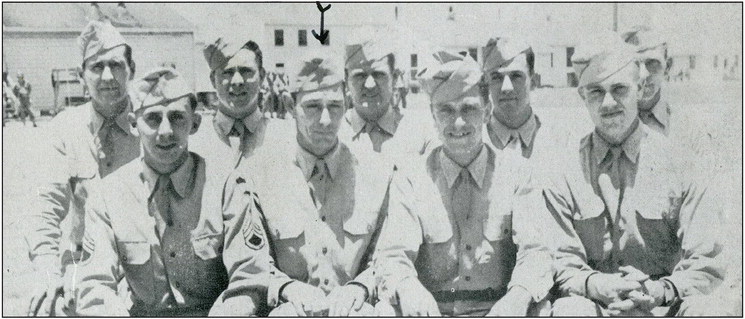

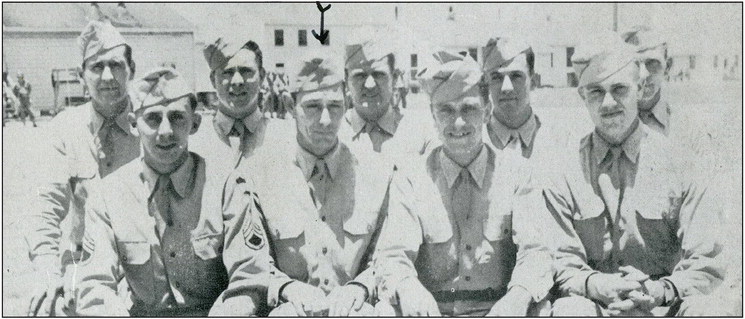

While he is no longer living, his daughter, Judy Simpson, Conrath, recalls facts gleaned from her dad’s time serving in World War II, beginning when Moore was drafted in 1942. To start, Moore was 34 years old at the time, much older than most of the other soldiers in the 99th infantry.

He also was responsible for supporting his mom and dad, and a two-year-old son, but when Uncle Sam calls, you answer.

“And he had to just get up and leave,” said Simpson.

Moore was sent to Texas, for training, but didn’t go through the full training, as he already met some of the criteria (knowing how to shoot a gun and having a skill, in this case, working on large trucks). Once that was over, he traveled to France, but had to know how to swim.

If the soldiers didn’t know how, they learned fast, as rowboats were put out while the ship continued on.

“And you got thrown over,” said Simpson. Hopefully, a soldier could swim enough to get by to get to the rowboats and catch up with the ship. The “lessons” happened, because if a German sub attacked the ship, those aboard needed to be able to swim.

When Moore reached England, being a bit impish, he carved his name into a brownstone building. C.J. Moore, Bruce, Wis., USA. Years later, he received communication that the brownstone buildings were going to be torn down and if Moore wanted it, the brick with his name on it was his, but Moore wasn’t able to make the journey.

“To this day, it’s over there in some museum,” said Simpson.

Once Moore got in the thick of things, there wasn’t much time for impish behavior. Indeed, marching across dense forests of the Ardennes region, between Belgium and Luxembourg, survival was the thing foremost on Moore’s mind. During the trek, Moore and the 99th came upon an asylum while marching through the woods, where the residents were wandering around, with no shoes, in the sparest of clothes.

Apparently, the residents had been abandoned and were incredibly thin.

“They tried to help them by giving them food or whatever they could, but these people had no idea,” said Simpson. “My dad said the worst part was, he just had to keep on going.”

Never learning their fate, Moore assumed the residents froze to death, but knew that nothing that could be done, because orders were orders. That day defined that it wasn’t just the battle action that was hard for the soldiers.

Another occurrence was when they had what they considered a 30-day “holiday.” During that time, Moore became close to a Belgian family with a younger girl. However, it was a dangerous affair, as German soldiers often conducted surprise visits. Eventually, Moore and his infantry needed to leave.

“He found out, as they were coming back, that the Germans went in, and shot the man...or the woman, and tortured the other one, because they harbored my father,” said Simpson, adding they never learned what became of the girl Moore was seeing. “The guilt was just…he says it happened all over.”

In movies, it’s shown that Christmas cease fires take place, with armies laying down their weapons, toasting with eggnog and singing of carols.

“It really did happen,” said Simpson. Maybe no one actually shook hands over enemy lines, but Simpson says her father felt a sense of quiet and rest. It also gave them a chance to look for their wounded; if the wounded couldn’t keep up, they had to leave them behind.

“This stuff blows my mind,” said Simpson. Even after he returned from the war, Moore didn’t like to celebrate Christmas. Simpson’s mom made sure they had a tree and presents, but Halloween was big in their household, as Christmas was a reminder of a time Moore didn’t want to think of.

“He just couldn’t do it,” said Simpson. “He did his best for us.”

Moore’s company was among those in charge of “setting up” for the battles, on direction of the higher ups. At times, the soldiers barely stopped, which meant if one of the vehicles quit, they left it behind. Moore would follow the main company and work on the trucks that quit.

He never knew what would happen, though, as he might get the word to put down his ratchet and grab his gun.

“He said, the first time he ever pulled a trigger, he’d never forget that,” said Simpson. “The fighting was outrageous.”

Despite the many causalities on both sides, Moore made it through the Battle of the Bugle, with no visible wounds. Others that he grew up with, weren’t so lucky, nor were the people of those foreign countries.

Moore’s company would set up mess tents to eat in, and refugees or natives, maybe both, would scrounge through the garbage, looking for any scraps to feed their starving families. Recognizing this, the soldiers would empty their trays into various pots and set them out for the starving people.

Simpson says one night, her dad was out there when a couple came up with some kids and he told them to just take the food that was in the pots. A few nights later, those people gifted him with German silk tablecloths with the napkins and two silver rings.

“They left them out there, because they were grateful,” said Simpson, who still wears the rings and has the tablecloths. “There was nothing left.”

When the German army came through there, they killed the animals or people left them to die as they fled. Moore brought back a piece of hide from one of the dead animals, that he had made into leather.

Perhaps the most horrific thing for Moore, was when they came upon concentration camps.

“He said the smell was so bad, of the dead bodies,” said Simpson. “This stuff sounds unreal, it really does to me.”

Simpson, who served in the Army herself, including spending some of her reserve duty in Cornell when there was still a station there, says her dad didn’t share much about his time in World War II. Moore came home with an EAME Theater Ribbon, with three Bronze Battle Stars; one Service Stripe; one Overseas Service Bar; and a Good Conduct Medal, but Simpson never knew how much the war really affected him, until he was near his death in 1994.

Even then, Simpson isn’t sure why he shared what he did, after all those years of keeping things bottled up.

“I personally think he was trying to clear his conscience,” said Simpson.