Drawing on her Ukrainian roots, Cadott woman creates art to last a lifetime

By Ginna Young

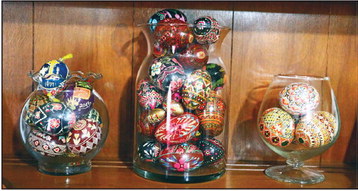

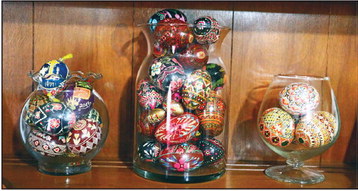

Using a writing tool, beeswax is melted and drawn in a design over the surface of the egg.

Multiple dyes are layered atop the other, while the desi...