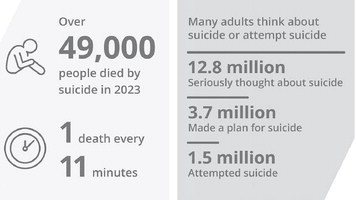

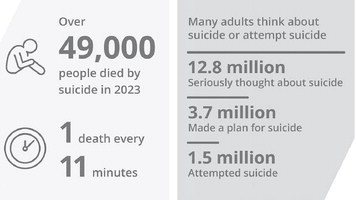

Human Services reports spike in young people considering suicide

More children are contemplating and carrying out suicide than ever before, and the recent discovery of a suicide pact among school-aged kids in Clark County has left mental health professionals, teach...