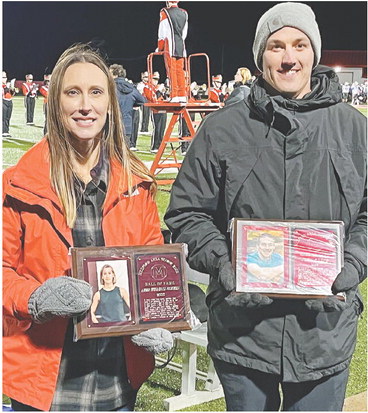

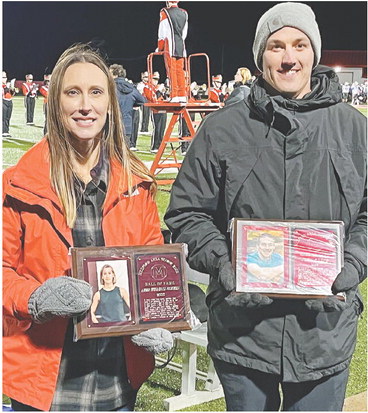

Keefe, Jochimsen newest additions to Medford’s Athletic Hall of Fame

MEDFORD HALL OF FAME

Membership in Medford’s Athletic Hall of Fame has grown by two with Friday’s induction of 2000 graduate Amber (Wiinamaki) Jochimsen and 2013 graduate John Keefe as part of the school’s homecoming festivities.

The new Hall of Famers received their plaques during halftime of the Medford football team’s loss to Mosinee and were treated to a community social event after the game at The Sports Page Bowl and Grill.

Jochimsen completed an athletic rarity in Medford by lettering 12 times in her four years as a high school studentathlete. She earned four letters in cross country, basketball and track and turned her success into an athletic scholarship to run cross country at UW-Green Bay.

Her accolades as a Raider included two state qualifications in WIAA Division 1 track, one in the 800-meter run as a freshman in 1997 and one in the 1,600-meter run as a junior in 1999. Also in track, Jochimsen once held records in the 1,600and 3,200-meter runs and was part of a school-record time in the 3,200-meter relay. She also held school records in basketball for career and single-game assist numbers.

In cross country, Jochimsen was an All-Lumberjack Conference performer all four years. Between all sports, she was a member of six Lumberjack Conference championship teams. She also was a national nominee for the Wendy’s High School Heisman award.

Keefe also was a multi-sport standout in his four years as a Raider. He lettered 10 times in football, tennis and basketball with basketball being the sport he was most known for. After graduation he went on to become a key member of the UW-Stout men’s basketball program, where he earned All-Wisconsin Intercollegiate Athletic Conference honorable mention awards twice while scoring 1,150 points, dishing out 285 assists and ranking fifth in school annals with 172 3-pointers.

In Medford, Keefe was a four-year starter in basketball, scoring 1,079 points. He holds the single-season school record for assists with 140 in his senior season and is the school record holder in career assists.

In tennis, he qualified for state in doubles as a sophomore with teammate Zak Barnetzke and he qualified for state in singles as a junior. A knee injury at the end of his senior basketball season ended his chances of making a third state trip. He was the GNC’s Single Player of the Year in 2012.

A late addition in his high school days to the football program, he excelled there too as a defensive back, garnering All-Great Northern Conference and All-State honors in his senior year when he intercepted a school-record 10 passes. He is still the program’s career leader with 13 picks.