Is this the face of justice?

PART TWO OF A TWO-PART SPECIAL INVESTIGATION

A county jail crisis starts with City of Wausau policing patterns

Marathon County’s justice system operates at the brink of crisis. The mass of people arrested by county law enforcement agencies are low income, unable to afford an attorney. The local state public defenders office often fails to promptly provide these “indigent” defendants with lawyers. These inmates must wait for their day in court. People with mental health issues are also arrested in large numbers. Unable to get treatment, these defendants return to jail again and again. The county jail in Wausau overflows with inmates.

The justice system can’t handle all of these defendants. The system grinds to a crawl, cases linger and the cost of running the jail escalates.

The result is that justice is delayed to the point of denial. The county jail is filled with people not serving a sentence, only waiting for trial or routine hearings. Marathon County Sheriff’s Department Corrections Division administrator Sandra LaDu reports that out of 283 inmates in the Marathon County Jail on Aug. 5, only 63 were serving sentences.

County leadership has tried to address the problem. Over the past few years, law enforcement has dramatically cut back on people it sends to jail. Many low risk defendants are not transported to jail, only given a date to show up in court.

The county hires lawyers for low income individuals. The county in 2021 spent $724,422 on legal assistance for resource-strapped people, including $310,820 on criminal attorney appointments.

Still, the county jail overflows with inmates. Unable to find room for prisoners in its downtown Wausau jail, the county houses defendants in the Columbia, Taylor, Lincoln and Marquette county jails. On Aug. 4, there were 13 inmates who had spent over a year in jail, including one who had been there for 1,152 days.

Jail overcrowding puts pressure on the county budget. The cost to house, feed and provide health care for people awaiting trial is proving increasingly burdensome. The monthly cost of providing medications (including mental health prescriptions) to Marathon County inmates soared to $44,195 in July of this year. The cost of providing mental health medicine for one inmate in a single month was $6,600.

Root causes

The causes for the courthouse backlog are complex. Some originate in the courthouse. Cases with police officer video camera footage, for example, require more time to prepare, slowing the wheels of justice. The COVID-19 pandemic created a court calendar backlog not just in Marathon County, but statewide.

Other causes, however, are outside the courthouse. They originate in who law enforcement arrests.

In Marathon County, a key reason behind the courthouse’s clogged court docket is that law enforcement, specifically the Wausau Police Department, arrests and brings to jail more low income defendants than the local eightattorney public defenders office can represent in a timely manner.

The number of low income people arrested in the county is surprisingly large. While the U.S. Census only counts 6.7 percent of county residents in poverty, the Wisconsin State Public Defenders Office reports that 85 percent of those prosecuted for felonies and 65 percent of those charged with misdemeanors are poor enough to qualify for a state-appointed lawyer (earning less than $15,629 per year for a single person without assets).

The Wausau Police Department arrests a large number of low income people because of defendant behavior, but also because of how it polices the city. Low income parts of the city are policed more than more affluent areas.

In Wausau, the police, in a practice tracing back to the 1960’s, patrol the city in six sectors labeled A through F.

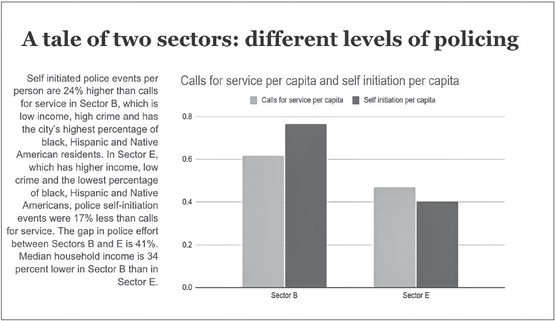

Data obtained from the Wausau Police Department shows that the department expends more effort policing the city’s lowest income sectors, B and D, compared with its more affluent sectors. The effort tracks with a higher crime rate in these sectors, but is out of sync with citizen calls for service.

Self-initiated Wausau police events (i.e. traffic stops and field interviews) in 2021 were 24 percent higher than calls for service in Sector B, which includes the city’s downtown and adjacent lower income neighborhood to the east. That can be compared to the police effort documented in the more affluent Sector E on the city’s far west side, which includes strip malls and an industrial park. This sector experienced 17 percent fewer police self-initiation events than calls for service. The gap in police effort between Sectors B and E is 41 percent. The median household income in Sector E is 34 percent higher than in Sector B.

This pattern of policing has, if only indirectly, a racial outcome. Like many other police departments across Wisconsin, the Wausau Police Department arrests many more black people, for instance, than occurs as a percentage of the general population. The Wisconsin Incident Based Reporting System reports that in 2020 black people accounted for 14 percent of Wausau Police Department arrests, although black people are less than one percent of the population. The City of Wausau GIS department reports that the highest number of minorities, including Asians, blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans, live in the city’s three less affluent sectors, B, D and F. These are where crime rates are highest and where the police expend most of its effort.

Wausau Police Chief Ben Bliven acknowledged in a May interview that different sectors of Wausau get different levels of policing.

“Your data is accurate,” he said. “Nothing is inaccurate.”

Bliven said, however, that he could not comment on the disparity without more information. He said his depart-ment planned to hire the Collaborative Reform Initiative for Technical Assistance (CRI-TAC) in Washington, D.C. to review its arrest history. He added that the city’s sector policing practice would also be reviewed by the Wisconsin Law Enforcement Command College at UW-Madison.

Bliven stressed, however, that officer racial bias has nothing to do with his department arresting a greater percentage of minorities, including blacks, Hispanics and Native Americans, than the general population.

“I am confident that the disparities in arrests are not the result of racist police officers,” he said. “We hold our officers to a high level of accountability. I know for a fact that we don’t have racist police officers.”

Compounding the problem

There is a second, non-courthouse reason for a backed-up county justice system. It is that police, again, specifically the Wausau Police Department, don’t just arrest mostly poor people, but it also arrests many mentally ill people. These people tend to repeatedly cycle through the jail. The Wausau Police Department might be thought of as a crime fighting agency. That’s not quite true. It is more a mental health unit.

Department data documents that in 2021 Wausau police officers responded to 822 significant crime events (within the categories of buglary, criminal theft, fraud, robbery, sexual assault, theft from a motor vehicle, threat with a weapon and stolen vehicle). The agency in the same year, however, dealt with more cases of mental illness. It responded to 856 cases of “mental subject.”

The data shows that in Sectors B, C and E, police responded to more cases of “mental subject” than significant crime, while it was the opposite in the other sectors.

On July 14, Marathon County Sheriff’s Department Chief Deputy Chad Billeb told county board supervisors that mentally ill people are a significant part of the county’s jail problem. He said these defendants “get lost in the shuffle” and sit in jail waiting for court hearings, all the while being stabilized by costly taxpayer-funded prescriptions.

Billeb said these individuals, many dealing with illegal drug addictions, are heavy users not just of resources at the jail, but at North Central Health Care, the Aspirus Health Care emergency room and the Wausau Fire Department.

The chief told supervisors these individuals cannot live independently and, once released from jail, reoffend and return to jail.

“Police are dealing with that [mentally ill] person over and over and over again,” he said.

Billeb said the sheriff’s department and Wausau Police Department have two Crisis Intervention Team officers, but the needed case management for mentally ill, poor defendants is not available.

“Case management with North Central Health Care is nonexistent,” he said.

Given all of these problems, supervisor Tony Sherfinski, Schofield, asked Billeb whether the criminal justice system was performing well.

“With all good intentions, is what we are doing working?” he asked the chief deputy.

“No,” said Billeb flatly.

Rebecca Erickson-Boe 862 days in jail pre-sentence

Alan Wilson 935 days in jail pre-sentence

Jesse Ingalls 683 days in jail pre-sentence

UNDER SCRUTINY-Pictured is a streetscape in Sector B in the City of Wausau, which gets more police self-initiated events (i.e. field interviews and traffic stops) than calls for service.

Ben Bliven

Chad Billeb