Is this the face of justice?

PART ONE OF A TWO-PART SPECIAL INVESTIGATION

County inmates wait weeks, even months for legal representation

U.S. Constitution Sixth Amendment “In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall….have the assistance of counsel for his defense.’ Wisconsin Constitution Section Seven of Article One “In all criminal prosecutions the accused shall enjoy the right to be heard by himself and counsel….”

All Americans have the right to a lawyer if arrested for a crime. In Gideon vs. Wainright, the U.S. Supreme Court in 1963 ruled that Clarence Earl Gideon, too poor to hire an attorney, had to be retried with the benefit of counsel in a case where he was accused of breaking into a bar in Panama City, Fla. Gideon, finally represented by an attorney, was acquitted of the alleged crime in the new trial.

The right to counsel is a basic American freedom. But this right is not necessarily extended to all Marathon County inmates.

Adam Plotkin, legislative liaison for the Wisconsin State Public Defenders Office, reports that on any given day there are approximately eight people sitting in Marathon County Jail who qualify for a state appointed lawyer but who are not provided one.

The reason is simple. Law enforcement arrests more low income people in Marathon County than there are lawyers to represent them. The Wisconsin Department of Justice reports that all law enforcement departments in Marathon County arrested 3,859 people in 2020. Among those arrested, the Marathon County District Attorney’s Office prosecuted 2,645 individuals for non-traffic crimes: 1,372 people for felonies, another 1,273 for misdemeanors. Among those prosecuted, according to Plotkin, 75 percent were “indigent” or poor enough to qualify for a state-supplied attorney (earning less than $15,629 a year as a single person without assets). Eighty-five percent of those charged with felonies were “indigent.”

The Wisconsin Public Defenders Office in Wausau has a staff of eight attorneys. They are responsible for competently representing these hundreds of clients. The result is predictable.

The Marathon County justice system is overwhelmed. There is a waiting list for lawyers. As a consequence, the constitutional right to counsel is recognized, but often delayed to the point of denial. The Wisconsin Supreme Court looks the other way.

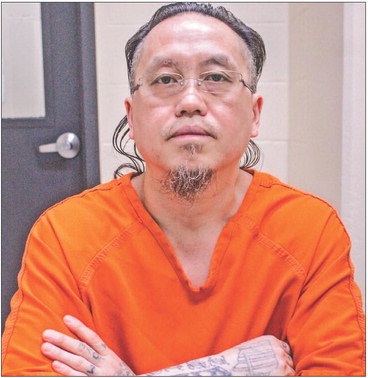

Take, for example, the case of Nhia Lee, a 46-year-old Green Bay man. The Marathon County Sheriff’s Department arrested Lee on Sept. 1, 2018, and charged him with two felony drug counts and a single count of identity theft.

He had an initial appearance on the day of his arrest. Judge LaMont Jacobson found probable cause to hold Lee in the county jail and set cash bail at $25,000. It was determined Lee qualified for a public defender.

Wisconsin law requires anyone held in jail on a felony charge with $500 bail or more must get a prelimi- nary hearing within 10 days. This is a proceeding where the state must prove there is sufficient evidence to hold a suspect in jail.

But Lee, lacking a public defender and unable to hire an attorney, did not get a preliminary hearing. Not for 113 days. The court continued to extend “for cause” the time limit for Lee’s preliminary hearing.

During that period, Lee asked Judge Jacobson to dismiss the charges against him. The judge refused. Instead, the local public defenders office sought to find an attorney for Lee. Over 100 lawyers contacted by the office declined to represent him.

Lee finally got his preliminary hearing on Jan. 2, 2019, before Judge Jill Falstad. Lee, now represented by Rothschild attorney Julianne Lennon, asked that charges be dropped. Falstad refused, saying there is no constitutional right to a preliminary hearing. She bound Lee over for trial.

Lee appealed his case to the Wisconsin Supreme Court, who, finding no error in the defendant’s treatment, ruled on May 24 that charges could be dropped and then refiled against him. It also ruled that Marathon County, which could have paid for Lee’s attorney, was under no obligation to secure his Sixth Amendment right.

In her dissent, Supreme Court Justice Rebecca Dallet said the county’s court commissioner erred in repeatedly extending the 10-day time limit for holding a preliminary hearing and that, in simply dismissing Lee’s case, the high court failed to protect the defendant’s Sixth Amendment right.

“The criminal justice system has already failed Nhia Lee twice, and by dismissing his appeal, we fail him as well,” she wrote.

She said circuit courts needed to order local counties to pay for public defender attorneys, especially in cases, like Lee’s, where the courts have improperly extended the time period for a preliminary hearing and a Sixth Amendment right is in jeopardy.

“The facts of this case are concerning, and reflect a breakdown in our system of appointing attorneys for indigent defendants….,” she wrote. “Circuit courts should…seriously consider using their power to appoint counsel at county expense, especially when they find the delay is very, very close to a constitutional violation.”

Her arguments only stirred the ire of Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley, who, speaking for the high court majority, rejected Dallet’s call for “transformational change” in the state’s justice system. She said the high court should not impose a financial burden on counties.

“The principal policy changes for which Justice Dallet advocates are properly considered by the legislature, which possesses the power of the purse,” she wrote. “We don’t have this power, which is why we should decide cases and leave policy making to the legislature.”

Lee’s case drags on. The Marathon County District Attorney’s Office on June 20 dismissed the two drugrelated felony charges and one misdemeanor charge against Lee, but refiled the three charges. The court ordered a cash bond of $15,000. Lee continues to reside in jail and, having pleaded not guilty, awaits a jury trial. Since his arrest, Lee (as of Sept. 6) has served 221 days in prison (for a probation violation) and 952 days in the Marathon County Jail, a total of 1,173 days. He has been incarcerated for four years. In Marathon County government, many officials are discussing how low income defendants can’t get lawyers, but not many will take questions from the press about Sixth Amendment rights in the county courthouse. One official willing to go on the record is Marathon County Sheriff’s Department Chief Deputy Chad Billeb. “The Marathon County Jail has a population of inmates who struggle to obtain legal counsel and are currently using limited space and resources within the jail,” he said. “Marathon County has assigned a court commissioner to assist in reviewing their progress in obtaining an attorney in an effort to move cases forward. Unfortunately a lack of defense attorney resources hampers progress and many of these inmates sit in our facility for very long periods of time.”

Another official, Marathon County Judge Suzanne O’Neill, a former public defender, told members of the county’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee on July 21 that the lack of attorneys willing to represent the poor is a big problem, not just for the defendants but for the entire justice system. “The public defender situation has been in crisis mode for a decade,” she said. O’Neill did not respond to a request for an interview with this newspaper. She, however, told the committee that while raising the pay rate for public defenders from $40 to $70 per hour in 2019 has helped the state recruit attorneys, it is often impossible to find the needed lawyers for the poor.

O’Neill said Marathon County pays attorneys $100 an hour to represent low income defendants, but, because the county has a dire shortage of criminal defense and family law attorneys, defendants are often not promptly represented. She advocated a program where the county would incentivize lawyers to move to central Wisconsin.

Marathon County Board of Supervisors vice-chairman Craig McEwen, Schofield, told the same committee meeting that the public defender problem was “at a crisis point right now.” He said the county was unable to afford paying for the health care of county inmates incarcerated for long periods of time. The cost of mental health medicines, he said, was especially troubling to county budget crafters.

McEwen also declined to be interviewed by this newspaper.

No comment

The Marathon County justice system holds defendants accountable for wrongdoing. Law enforcement arrests suspects. The District Attorney’s Office prosecutes them. Judges sentence the guilty to jail and order fines be paid.

But what happens when the justice system itself is overwhelmed and fails to guarantee the basic rights of defendants? Is the system itself accountable? We asked leadership in the county justice system for comment on this story. Marathon County Presiding Judge Michael Moran, Sheriff Scott Parks and District Attorney Theresa Wetzsteon all declined comment. The county board rules approved in April that task the Public Safety Committee with “evaluating programs and services to foster the fair and impartial administration of justice.” All members of the committee, including its chairman Matt Bootz, town of Texas, however, declined comment. The county board rules further say that it is the responsibility of the Executive Committee to review the work of the standing committees, including the Public Safety Committee. County board chairman Kurt Gibbs, town of Cassel, who chairs the Executive Committee, declined comment on this story.

It is the job of the Assembly Committee on Criminal Justice and Public Safety to oversee justice systems in all 72 state counties, including Marathon County. Chair of that committee is local assemblyman Rep. John Spiros (R-Marshfield). The legislator was asked for his viewpoint on the shortage of county public defenders. He declined comment on this story.

It was local supervisor Chris Dickinson, Stratford, who wordsmithed the county rule approved earlier this year talking about the county justice system providing “fair and impartial administration of justice.”

But would Dickinson respond to questions about whether the county was following the very rule he drafted?

The supervisor said he had no comment.

Rebecca Dallet

Suzanne O’Neill

Chad Billeb